Listening is probably the most important part of communication.

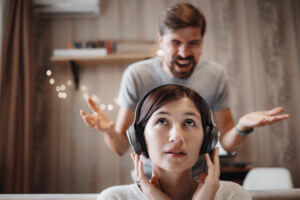

And yet, in the era we live in, it has become a forgotten art.

The hustle and bustle of modern life and social norms mean that interactions with other human beings bring “noise” from all parties engaged in conversation.

Try observing people engaged in conversation and you will see that it is very rare for one of them to be silent for very long. Polite society dictates that we make small talk, the normal prelude to conversations at a deeper level; we, the English, are sublime in our ability to fill the silence with subjects such as the weather, football or last night’s episode of X Factor. This cacophony of noise is, in fact, getting in the way of communication. A lot is being said, but not much is truly heard.

There are two basic parts to any communication, firstly, what is being transmitted, and secondly, what is received. If we are busy filling any silences due to pressures of wanting to be polite and engage with people, as is the social norm, then how much of what is being transmitted is actually being received, and at what level of detail?

In a training environment, this can create great difficulties if we only really hear part of the message or if we are not truly tuned in to the transmission. By that, I mean really listening in an active way. We learn as trainers to compensate for the lack of message content by second-guessing or using our experience and knowledge to “fill the gap”.

There is a different (better?) way to tackle this, and there are two aspects to it. The type of question used and the type of listening we do after asking the question.

As trainers, we often feel we are listening and, in fact, are good listeners (I used to count myself as a really good listener), but the reality is quite often, we may just be silent and wait our turn to speak. Or worse still, being silent, thinking about the next question we are going to ask, that will surely get our learner to where we both wish to be.

We are trained as driver trainers to ask questions mostly designed to furnish us with the answer that we wish to hear, for example, “How might you have negotiated that last roundabout better?” or “What do you think would improve that last junction emerge?” these are questions that are designed to get the learner to tell you what you already know, i.e. if they did x, y or z that it would improve things.

This is a very limited form of questioning which reduces the number of possible answers the learner can give. We often then complicate things further by asking supplementary questions, asked with the best of intentions by an eager instructor to give clarity to what they want, or sometimes to correct a badly phrased question; it is often the case that 4, 5 or even 6 questions are asked, leaving the poor learner confused as to which particular question they should answer.

The type of question outlined above is designed to have the learner find out for themselves what you would have told them otherwise, and in this way, they will learn (and they will). However, there is a form of questioning that can be used that will enable instructors and pupils to find solutions to issues that really cut to what the problems are. The type of questioning outlined above is almost learning by rote!

What we need is real learning to take place and solutions to issues discovered by the learners themselves; in this way, the solutions will seem more relevant to the learners, and they are more likely to stick with the solution they came up with themselves. So to get to this, we need to ask questions that we, the instructor, do not know the answer to ( a coaching question), and they would be questions along the lines of “How did you feel as you negotiated that last roundabout?” or “what were you thinking while we drove out of that junction?”

As the instructor, you do not know the answer to these questions, and yet the answer to the question will surely unlock the learner and un-stick them from the plateaux they may be on.

The secret is in what we do after the question is asked, how we listen is critical to better outcomes for our learners as well as us as instructors. There are several levels of listening, but only the upper level of proper “active listening” will yield the results we are looking for.

Take the time next time you are in a coffee shop or a pub and watch the interactions between people, and you will see the various levels of listening on display; the body language of the person “listening” will almost give away what sort of listening they are doing.

Level 1 – Not Listening

Body language signs

- The body turned away slightly from the speaker

- Glancing at watch

- Looking around the room

- No eye contact

- Arms folded

- Messing with phone/iPad

Overheard Conversation

Person 1 “I’m thinking of putting in for a promotion at work”

Person 2 “Did you see the footy on telly last night?”

or

Person 1 “I’m thinking of putting in for a promotion at work-”

Person 2 (interrupting) “I did that once. It was great I got the job.”

Level 2 – Half Listening

Body language signs

- Start off looking interested but then turn away slightly from the speaker

- Appear distracted by looking out of the window

- Switch from listening to taking over the conversation

- Limited eye contact

- Not sitting still (shuffling)

Overheard Conversation

Person 1 “I’m thinking of putting in for a promotion at work.”

Person 2 “I’ll tell you what you need to do.”

Level 3 – Attentive listening

Body language signs

- Looks interested in the speaker

- Maintains appropriate eye contact

- Head tilted to one side, demonstrating interest

- Sitting still

- Smiling

- Nodding

Overheard Conversation

Person 1 “I’m thinking of putting in for a promotion at work”

Person 2 “That’s interesting. Tell me more about that”

The final level is true active listening, where you are engaged with the speaker wholeheartedly, and are demonstrating it with your body language and the way you listen. It is important to make encouraging noises such as hmmm, ah, yes, I see (but not interrupt). Active listening looks the same as attentive listening, but it is different in the way things are followed up.

Level 4 – Active Listening

Body language signs

- Looks interested in the speaker

- Maintains appropriate eye contact

- Head tilted to one side, demonstrating interest

- Sitting still

- Smiling

- Nodding

Overheard Conversation

Person 1 “I’m thinking of putting in for a promotion at work.”

Person 2 “What is it that has prevented you from doing it?”

What then follows is absolute silence from person 2, who has just asked the question, which allows thinking time for person 1. The golden rule here is that only the person being asked the question can break the silence. As an instructor, you might find it very difficult to deal with silence, especially when your training has taught you to fill these silences with learning opportunities.

The Silence is the greatest learning opportunity of all as it allows clear, quality thinking time. It may be that the person being asked the question will respond, “I don’t know”, and this is fine because a follow-up question can then be asked, a question such as “If you did know what would you say?” or “what would your best guess be?”

Try not filling the silence and see what results it is possible to achieve by giving the learner (and you) some clear blue thinking time.

The previous conversation started, and an active listening level may pan out in a surprising way if you allow it the right time and space and ask very thoughtful questions.

For example:

Person 1: “I’m thinking of putting in for a promotion at work”

Person 2: “What is it that has prevented you from doing it?”

Person 1: “Well it’s not easy to find the time, the boss and I have such busy schedules”

Person 2: ” What can you do to try and nail down an appointment?”

Person 1: “I suppose I could get my secretary to organise it with his PA,but I don’t like to ask”

Person 2: “What is about asking that you don’t like?”

Person 1: “Well he might say no!”

Although the example used does not relate to driving instruction, you can see that by asking questions that you do not already know the answer to and by listening more, we can uncover things that we wouldn’t otherwise.

In a learner-driver context, it may work by finding out the feelings that are underlying any issues, for example.

Instructor: “How did you feel negotiating that last roundabout?”

Pupil: “Terrified!”

Instructor: “What was it about it that terrified you?”

Pupil: “I just feel overwhelmed because I have so much to think about all at once!” Instructor: “Is there anything I can do to help you with that?”

Pupil: “Could you show me how you do it?”

You will likely (given enough silence following the question) come up with a level of help that they feel would be useful to them. Don’t assume they don’t know because, given the chance to think for a little while (silence is golden), they do!

Try it and see!